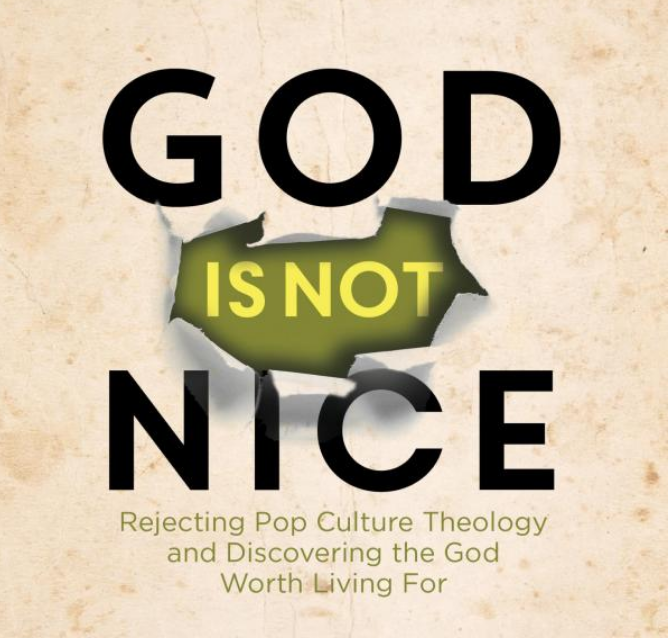

In his new book God is Not Nice (Ave Maria Press), Ulrich L. Lehner—a professor of religious history and theology at Marquette University—makes the case that for too many people in the West, God has become a personal life coach, a counselor, or even benign grandfather, rather than the awe-inspiring, untamed, demanding God that he truly is. The worshipping of a “nice” God has led to many of our culture’s ills, according to Lehner. Catholic World Report talked to him about his new book.

Leslie Fain, for CWR: What prompted you to write this book?

Ulrich L. Lehner: Countless students of mine went through 10 years of Catholic schooling, or more, but had no clue that God really desires them to be saints. They had no concept of a God who works in their lives, who makes demands, but who also promises a complete transformation. In short, they had been fed the lie that they can live on their own, make up their own moral standards, and use God as a glitter for weddings and First Communion, and in times of despair. They live as if God were dead, but resuscitated him when needed; God is a commodity to them. I asked myself: How can I make clear that the Christian life they find so boring is just a caricature, and that it is their lives which lack any real substance? That’s how the idea for the book was born.

CWR: What is a “nice God” like, and how does he differ from the God taught by the Catholic Church?

Lehner: The nice god (I don’t use capitalization here to make the difference clearer) is one created in our image and according to our needs. He allows us to live comfortable lives, but he is not expected to take care of us, because we were taught to be self-reliant, doing things our way, never to think of [ourselves] as failing (e.g., Norman Peale, The Power of Positive Thinking—an apostle of the nice god just as much as the prosperity gospel preachers). Of course we wouldn’t want our kids to say “I am a failure,” but Christianity believes that deep down something in us is so severely broken that we are failures without God, cannot walk a straight line without him, achieve no real greatness without his grace. In Catholicism you see the difference every time in Mass at the Confiteor, where we confess our sins to the entire community—we admit we fail constantly—or through Confession. The nice god gives us the illusion that we are always winners who don’t have to apologize, or victims who cannot do anything wrong (the nice god has a double face!)—that we are basically morally good because we haven’t committed murder. This last sentence I’ve heard countless times from students—many believe they are good because they haven’t committed homicide, yet they don’t give a thought about the darkness of the hook-up-culture, alcoholism, pornography, etc.

CWR: When a church adheres to the theology of a “nice” God, how is that reflected in the homilies, liturgies, and witness of the clergy and parishioners, in your experience?

Lehner: I have heard the nice god being preached at Catholic churches. We are told that we should be “nice” to each other. Every person should be treated with respect, of course, because all are created in Gods image, but if we were told that this is the only thing necessary to becoming “good people,” we know we are listening to a disturbed pastor. We cannot be good without God interrupting our lives, transforming us—and that is only possible by surrendering to him and his grace, by acknowledging our sinfulness and our need of the sacraments. If god is just the icing on the cake, it’s not the real God. If our Catholic faith is limited to one hour a week, it shows that it has dissipated. Imagine living with your spouse day in and day out but only talking to her 50 minutes, once a week! I don’t think anybody would consider this a healthy marriage.

I have also met priests who prided themselves on “liturgy free” days: they were happy not to celebrate Mass on those days and have a day off. I wondered whether they abandoned the breviary on those days, too (since praying it is the Liturgy of the Hours!). Others said they would go on vacation only where they would not be recognizable as priests. I was shocked; the older priests in my parish would drag themselves up to the altar to celebrate daily, no matter what.

CWR: In a parish where a priest worships and preaches about the true God, not a “nice” one, what would the typical Mass look like? What would the witness of the priests and parishioners look like, most likely?

Lehner: St. Brigid of Sweden once had a vision she asked her confessor about. She saw two monasteries. In the first one, the nuns were fighting devils who tried to enter through windows and doors. It was a place of battle. The other monastery was a quiet, deadly silent place. Her confessor said: “In the first monastery faith fights the devil, in the second Satan has already won and the fight is over.” We are saints in the making, and thus struggle until we die. The nice god is not always easily detected and is often shrewdly disguised under buzzwords of “compassion” or even orthodoxy. Yet, whenever we are not putting [ourselves] and our affirmation at the center, but worshipping the true God, we encounter his mystery. For that our parishes need, as Cardinal Sarah says, silence. Without meeting God in silence we don’t know him, cannot be transformed, and ultimately give in to evil and temptation (as the vision of St. Brigid shows).

CWR: You trace this theology of niceness not to the Reformation, but the Enlightenment. Would you explain how Enlightenment thinking led to this flawed view of God?

Lehner: I have learned a lot from my Protestant friends, especially how to love Christ, the Word of God, and abandoning oneself to God’s providence. The Reformation was heavily anti-Pelagian, and thus against the idea that we can make it to Heaven our own way. In the Enlightenment, however, the idea of Original Sin was abandoned. Humans were suddenly seen as basically good. God was no longer needed to transform our lives; instead he became a distant being. Last but not least, the Enlightenment destroyed the idea of the common good and natural law, and Rousseau replaced both with sentimentalism. It is this sentimentalism that reigns today (you do what “feels” right, not what “is” right).

CWR: What, in your opinion, causes people to follow a “nice” God when, as you explain in your book, the journey is ultimately unsatisfying?

Lehner: It is the most comfortable religion you can find. It makes no real demands on you, and you take it from the shelf whenever you “need” it.

God becomes the aspirin pill in times of grief and pain, but is abandoned when such times are over. Ultimately the real god is the “god of consumption.” Parents have lost their kids to the mall, not to Christ.

CWR: What can you do if you live in a diocese in which the bishop follows and preaches a “nice” God? Is there any way to try to turn things around?

Lehner: I am a great fan of the Carmelite writers, and all the masters agree that renewal is necessary. Since we are all called to live according to Christ’s commands and his love, a good place to start this renewal is with ourselves and our families. Being renewed in Christ also means suffering for him; St. John of the Cross was imprisoned by his superiors! This, however, did not deter him from speaking up for what Jesus commanded him to do. In all of this he knew the “reform” was God’s work: it is Christ’s Church, not ours—and he will provide as long as we cling to him.

CWR: You use an array of adjectives to describe the true God, including the word “wild.” Could you explain what you mean by that?

Lehner: Wild means un-tamed. Yet, today many attempt to tame God’s involvement in our lives—we shut him out and his grace. Modern humans are control freaks (and I don’t exclude myself from that temptation!), but when we try to control God we effectively turn our backs to him. With God there is freedom, life, fulfillment, adventure—that’s why Heaven will never be boring!

CWR: How do priests preach about a God who is “not nice” in a culture like ours, which seems offended by most everything?

Lehner: We all have two passports, one for our citizenship, but the more important one is the one for Heaven. Every citizenship comes with obligations, not just rights. Yet many do not want to change their lifestyles accordingly. I think priests have a hard enough job as it is and most try their very best; it is the parents who have to convert most. As long as we teach our children that what is true for you might not be true for me; that whatever you feel good about must be right; that as long nobody is hurt all is fine; that hooking-up, porn, etc. is OK as long as it consensual—we cannot expect our churches to change.

What parents today lack is the virtue of fortitude to stand up against the culture of death, which disguises itself as the culture of compassionate sentimentalism. Unmask its emptiness, live a life that attracts others to the Good News, inform yourself about the richness of the faith (get your kids good novels to read), and don’t be afraid! Pray without ceasing to the Holy Spirit for good counsel and fortitude.

CWR: Do you think that “nice” God theology is here to stay? Why or why not?

Lehner: It will stay as long as humans live. It feeds on our original sin: our egoism. As long as we put feelings before truth, it will have a powerful hold on culture.

CWR: Do you think the worshipping of a nice God has led to any of the ills we are currently seeing in our society? If so, how?

Lehner: Once we worship the “nice” God, we give in to sentimentalism and emotivism (“whatever feels right is right”), and consequently, we lose contact with reality and the order of creation. If we don’t accept God’s order, we impose on everything around us our idea of order; however, our self-made order is an illusion built on our desire to have good, pleasant feelings. We don’t want to change our lives, [nor] a God who reminds us that we should. We see the results all around us: people who do not want to bear the consequences of their actions, who cannot control their desires because they never heard that they have to be controlled or purified, who deny God’s Word having any demands on our life beyond “feeling compassionate” or [being] “consensual.” If you read Holy Scripture, I don’t think you will find a verse in which God asks us to “feel” anything; feelings change; he asks us to choose him and follow him. That’s why the nice god drowns prayer with activism—there is no place for contemplation and for meeting the real God anymore.

I have witnessed this countless times at my (Catholic) university. Our students had to fight for having the opportunity of Adoration; once they were allowed that, there was no monstrance on campus (a Jesuit university). So the students had to raise the money themselves to buy one, while tens of thousands of dollars were spent on all kinds of activist events. Contemplation is the biggest threat to the nice god.